If you follow instructions from your convoy leader, you are less likely to make a mistake that will lead to a warning or suspension.

"Four north on 49, last one is wide."

"OK convoy, we have a wet spot right after the portage, and security is making sure we're staying at 10, then we'll be back to 25 at the half-K sign. Keep your spacing in the slow zone."

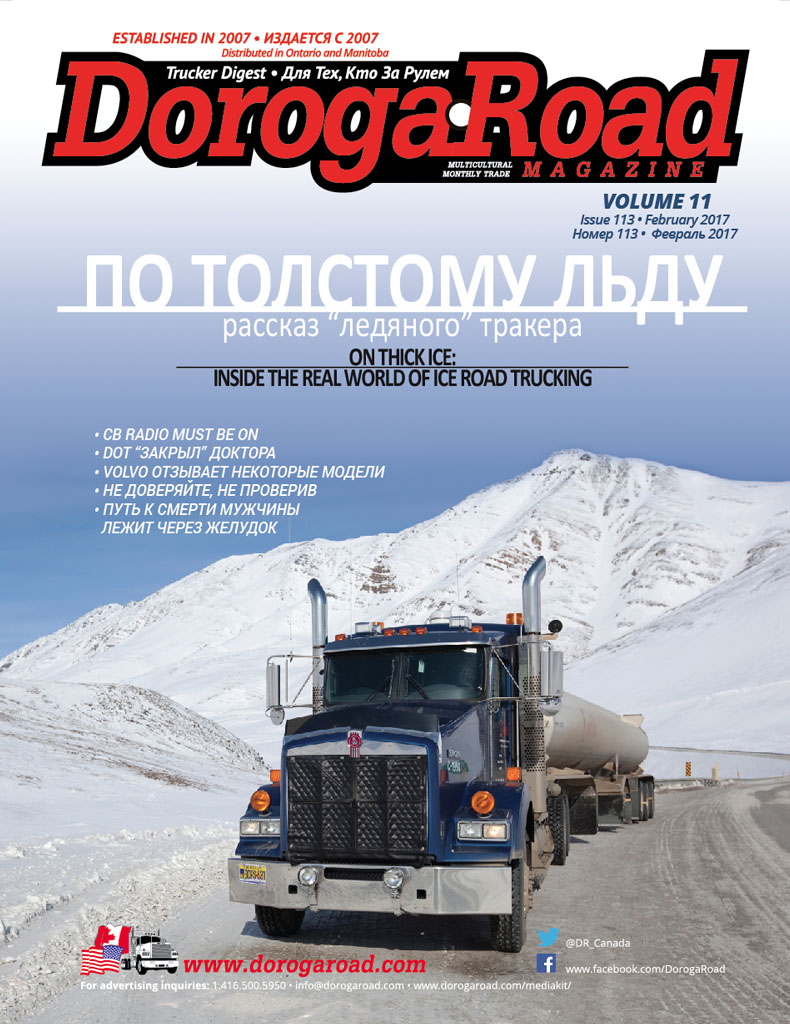

The instructions over the radio sound like a convoy operating with military precision, and it is that very thing. Mine resupply in Canada's Arctic is an operation that lasts approximately two months in late winter. It is busy, closely monitored, and has no room for error. About 85% of the "road" itself is floating on water, with anywhere from 500 to 800 trucks cruising on top; the main stretch is 400 kilometers long, branching out in spurs to various mines.

This is extreme trucking that few in the world get to experience. And it is essential to the economy in Yellowknife and the survival of the mines.

Every year since 1982 a road has been built over ice-covered water to bring supplies northward. It's been there so long that it is even found on most Global Positioning Systems. The route can change a little from one year to the next, but usually not by much. Once established it will support anywhere from 3,500 to almost 11,000 loads in a single season.

The skills needed to drive the route are familiar, but a demand to closely follow the rules is exacting. Some experienced drivers arrive in the north with a cocky outlook. Before you know it, they head home for good. The next driver may be a rookie with very little experience who takes to the job and returns for many successful years.

The pioneers of this road, and the ones in charge, have tested and proven what works safely. If you follow instructions from your convoy leader, you are less likely to make a mistake that will lead to a warning or suspension.

Long hours, little wiggle room

You must drive for up to seven hours with no breaks, all at 25 kilometers per hour. When loaded northbound you must slow to 10 kilometers per hour when heading on and off the ice, and follow the speed limit religiously. Even 27 in a 25, or 15 going on or off the ice, will net you a five-day suspension and loss of a safety bonus. There is very little wiggle room, and for good reason. A "blowout" where the ice cracks and water flows up onto the ice – caused by speeding or unsafe actions – can limit a road to really slow speeds, or in the worst case, close the road for the season.

All loaded northbound trucks are dispatched in convoys from Yellowknife every 20 minutes. A convoy consists of at least two, but usually four trucks. The first 70 kilometers is on a narrow territorial road that twists and leaps over and around small hills. Drivers are required to stay one kilometer apart from each other, so you rely on the leader calling out the mileage markers and gauging where you are in relation to that. Security patrols the road and watches speed and spacing.

Try to imagine that challenge. Narrow road. Each truck with different weights. Twists in the road only allow for an occasional glimpse of the truck ahead. Convoy leaders call out locations. Maintain your speed and spacing. It doesn't matter if you're perfect for 69 kilometers. If you slip up in the wrong place you could end up in the ditch or be suspended by ever-watchful security teams.

Some people can't handle the boredom. Hour after hour of avoiding cracks in the ice, straining to see through the blowing snow, hoping your truck doesn't die in the -40 Celsius temperatures or need a regen, takes it toll. Speed and spacing is the mantra. Follow the speed religiously and keep 500 meters away from the truck in front. Security is everywhere, and listening on the radio. They're in pickups, so they can travel much faster than you. It makes it seem like they're everywhere.

You do this for 60 days straight. Legally allowed 16 hours on duty per day, it is exhausting. No days off required. That's 112 hours per week. You get to the point that you want a road closure to get some extra rest, or voluntarily take a day off in Yellowknife.

Solitude, yet closeness

Constantly in a convoy with at least one other person, except in special circumstances. The solitude, yet closeness to the same people, can cause some to crack. No foul language, harassment or bullying of any kind is tolerated, whether from drivers or security or other workers. People who act like that are quickly weeded out.

During the season you'll probably spend some quality time stranded on a portage in a howling blizzard, trying to keep warm and hoping you don't have a case of diarrhea. (There are only two areas that have "bathrooms".) Cooking in a small area, no room for exercise, no one to talk to, except by radio which is constantly monitored by the authorities, and hoping the truck keeps pumping heat and that you'll have enough fuel to get to the next fuel stop. It is nerve-wracking.

The fear of plunging through the ice is hard for some to manage. This is despite the fact that no resupply truck has ever gone through the ice into the lake below. An ice worker vehicle has, but never the resupply trucks. It's an amazing safety record for the Joint Ventures that manage the road. Still, many drivers have gone home early, never able to get over the tension.

A good portion of the road is above the treeline, so it is like a barren moonscape. Harsh, but beautiful. It's wonderful to see the animals roaming or flying around. All of the land belongs to the Tlicho people and nature is king. If you throw a breadcrumb out the window to feed an animal, you will be immediately sent home and banned for life. Leave the land as you found it. The parking areas and the roads are scraped clean at the end of the season and disposed of in a safe manner. The portages, or land crossings, are the same ones every year and tend to be quite narrow. No more land is crossed than absolutely necessary. You are never allowed to approach wildlife or honk your horn to get it to move. Burial grounds are passed at slow speeds to respect the ancestors.

Road work

Construction of the ice road starts as soon as there is enough ice to support an amphibious vehicle that maps the thicknesses of the ice, using ground penetrating radar. These radar sleds are towed up and down the ice constantly until the season is practically over. This data is used to determine the weights allowed and where ice needs to be made better or thicker.

In an area of poor or thin ice, a crew will go out with a truck-mounted auger. Usually they set up in the middle of the 150-foot-wide road and drill holes several yards apart. Others in the crew take special water pumps and suck water from the hole. Like flooding a backyard rink, they pump water over the ice, one side at a time. Traffic will pass by at 10 kilometers per hour on the dry side. There are many crews constantly repairing the road 24/7. It's a great system and they do a tremendous job, all at temperatures that would frighten most sane people.

On any large body of water, pressure ridges can rise up and form as the ice freezes. This is where ice pushes together, forming an impassable peak. The crews work hard to reinforce the ridges and shave them with graders. Traffic here can be reduced to five kilometers per hour on a bad ridge. On rare occasions the road will have to steer away from the planned route to find a better place to cross the ridge.

Everyone sees the toll that heavy vehicles take on the roads made of cement and asphalt or stone. It's no different on the ice. A loaded truck will cause the ice to deflect up to three inches, creating a wave effect. Have you ever watched a train at a crossing and felt the road move up and down and the rails flexing? It is the same idea on the ice, except the "solid" roadbed is a minimum of 39 inches of ice. The approaches to portages are rarely straight in. They're curved to allow the wave to dissipate away from where you need to land. All of this flexing also causes cracks in the ice. These cracks can swallow a tire if you're not careful, so you watch.

Sometimes as you're passing near a crack, the flexing causes a snowball to pop up and skid across the ice. These chunks can literally be as big as basketballs, and if they haven't broken totally free, can present a real hazard. The ice workers highlight them with reflective paint so they're easier to see. If you're sleepy and one fires up under your truck, you certainly sit up a little straighter for a few minutes.

Keep moving

There are no special trucks here. Each trailer is loaded to the maximum allowed, either by weight or space. A Super B can be permitted 67,000 kilograms (about 3.5 tonnes more than most jurisdictions). Every vehicle must be stocked with -emergency rations, spill kits, and have a working VHF radio. Extra insulation and belly tarps are used to try and keep out the cold.

One rule is never to shut off your engine. If you are in fueling in Yellowknife you can shut down to check oil, but the hard rule is to leave your truck running. At -40 or -50 Celsius, it doesn't take long for it to freeze and not restart. No one wants to take the risk of freezing while trying to re-fire a truck.

At the end of the season you feel relief and may swear you'll never come back. If you've made it the whole season with no suspensions or incidents, you'll walk a little prouder. But just making it is an accomplishment no matter what. The bonds with the other drivers is never forgotten and will continue when you go back home.

It's brutally tough, monotonous, frigidly cold like you've never seen before, rules strict beyond belief, but the pay is decent.

Don't worry. You'll come back for -another "last" year just to do it all over again.

Newspaper about

Newspaper about